“Other than the Bible, which book has shaped you the most?”

I usually stall for a few moments (the people-pleaser in me wants to make it seem like I’m honoring the question by giving it some deep thought) and respond with Tim Keller’s Counterfeit Gods.

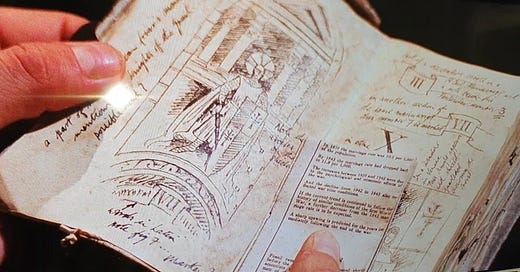

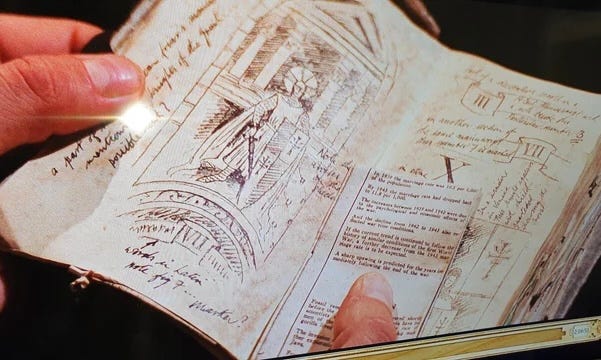

It was assigned reading for one of my seminary courses and it has not only changed my approach to ministry, it has shaped my view of God and altered the course of my life. This is not an exaggeration. I’ve read the book at least a dozen times. I have led small group studies with it at every church I’ve served. I’ve given copies away for many different occasions and the lone copy I have in my office is marked up and highlighted so much that it looks like Indiana Jones’ dad’s diary.

Despite the impact of the book in its entirety, there are three specific touchstones that have made a monumental impact on my life. The first is Keller’s treatment of the Abraham/Isaac sacrificial lamb narrative. The second is how Leah came to choose Judah as the name of her fourth son. The third touchstone is Keller’s explanation of the deeper idols of our hearts.

Keller writes that the surface idols—what many of us thought were the main idols—money, sex, family are instead symptoms of the deeper idols, to which he named four: power, approval, comfort, control.

“Each deep idol, power, approval, comfort or control generates a different set of fears and hopes. Surface idols are things like money, spouse, children, through which our deep idols seek fulfillment.”

This is not new information. We’ve preached from this paradigm. We’ve modeled our discipleship pathways according to its spiritual cartography. By now, we are all familiar with its definition and its subsequent mainstream applications.

For Asian Americans, however, I believe there is a fifth deep-idol: the desire to belong.

This is different from the idol of approval. According to Keller, "People who are motivated by approval...will gladly lose power and control as long as everyone thinks highly well of them." Approval is self-motivated and individualistic in nature. For Asian Americans, we won't gladly lose power and control so that others will necessarily think highly of us, ours is a deeply contextualized motivation of wanting to belong.

I can think of at least three reasons that this deep idol is so prevalent in our immigrant communities.

Racialization/Othering - If we are the perpetual foreigner in society, and if we are also limited by the bamboo ceiling in our workplaces, our 360-degree existence is characterized by being on the outside looking in. The result is a desire, a deep longing, to be included in the inner circle of any circle that will have us.

Cultural Vagrancy - many of us have taken trips back to our motherland and once the initial awe and aura has subsided, we are left with a really full belly from good food, but also a chilling realization that we still do not belong. We can’t place it, the feeling often escapes words, but whether it’s “Second-Generation”, “ABC”, or a “third-culture kid”, our vernacular often does a better job of defining our status than our feelings.

Parental Dissonance (especially true for the older Gen-X crowd) - many of us who do not speak the same language as our own parents, have a disconnected experience of belonging in the one place where this shouldn’t have been the case. Without the ability to communicate well with our parents, we instinctively looked to anyone in our community as potential parental surrogates. We learned life skills from them. They taught us how to put on deodorant. How to fill out a job application. How to respond to stimuli, and to varying degrees of detriment, how to cope with anger and stress. The result was a deep affection and an intense loyalty to these mentors for they provided us a temporal inclusion that wasn’t part of the makeup of our nuclear family.

Looking back at our shared lived experiences as Asian American immigrant children, we see that the desire to belong is nearly omnipresent. We are also aware that the deep idol of belonging supplies the motivation fuel for the other four deep idols. The reason we seek power or control is to create or maintain our own space of belonging. The reason we work so hard for approval or for comfort is to find a nestled place of acceptance. To this end, it’s particularly helpful to be aware of its explosive idolatrous potential when the desire to belong becomes the paramount motivation of our heart.

Two Avenues for Grace.

If the greatest commandment is to love God and love neighbor (Mark 12:28-31), Asian Americans are given a uniquely distinct avenue to fulfill this commandment through a growing understanding of this deep-idol of belonging.

Love God

My church (Home of Christ in Cupertino) has been operating from the ecclesiological understanding that “Church is Family.” Our website’s homepage displays a powerful message that speaks to the gospel remedy of this deep idol: Welcome Home. It's a big motivator for attendance in our programs and activities, the reason for potlucks and outings, it's why life-on-life works. We all want to belong.

While we don’t have this all figured out, the end-goal is to see our church family thrive in the long run, not just survive-and-advance. If one-half of the greatest commandment is to love God, the deep idol of belonging can only be fully satisfied within the context of a church family.

Love Neighbor

Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah write in their book, Unsettling Truths, that the key to reconciliation (or as Charles puts it, “conciliation, not reconciliation, because reconciliation implies that our country was united once”) is to build a common story.

Charles posits a common story for our country as one based not on a divisive narrative of power imbalances and racial injustices, but on the shared narrative of our collective actions as a response to trauma. Indigenous people groups and ethnic minorities operate from a sense of racial-PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder. Colonizers and white Christians, similarly, operate from a sense of PITS: perpetrator induced traumatic stress.

Charles concludes, “in treating white people as a traumatized people, people of color have the authority to maintain their own agency and humanity in a way that has not been accessible before. Oftentimes, in conversations on race, whites are viewed as those with power who should initiate the seeking of forgiveness and initiate the process of reconciliation and healing. Instead, by treating white Americans as traumatized people, we are called to an equality in our mutual brokenness and trauma.”

Oppression and othering, whether perceived or real, creates a desire to belong. To be “out of many, one.” While I denounce Christian Nationalism as one of the more grievous sins of our American society, the command to love all my neighbors is only made possible to the same degree that I can accept my own idolatrous desire to belong. If I can recognize its explosive nature and its detrimental hindrance of the gospel promises to my own community, then I can recognize its equally destructive effect on other people groups. Telling a common story.

In the next few weeks, our country will face certain divisions, politically and theologically. And greater minds and more forgiving hearts will need to parse this common story out in ways that are applicable and reproducible but, for me, it’s a start. A path to repentance and a way forward in obeying the Greatest Commandment.